adaask/iStock via Getty Images

In the wake of the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SIVB), Silvergate (SI), and Signature Bank (SBNY), many investors are wondering which banks may have the most significant exposure to a potential “contagion effect.” The focus has settled on First Republic Bank (FRC), which lost over 70% of its value over the past week due to concerns regarding its exposure to VC and PE financing, bank run fears, and unrealized losses on its Treasury assets. Other banks with similar issues could be at equal or greater risk than First Republic.

In my view, Truist Financial Corporation (NYSE:TFC) is a particularly interesting bank due to its high exposure to unrealized losses on Treasury bonds. Truist is much larger than most other banks caught in the “contagion fear crash” and, therefore, represents a much more considerable systemic risk than First Republic if it fails. Of course, various government stimulus efforts have fueled a rally in Truist and most banks as contagion fears fade. Additionally, many investors are interested in larger banks like Truist because they may manage to purchase assets at a discount or gain deposits from failed banks. TFC’s valuation is also significantly compressed, with a “price-to-book” ratio of ~0.85. Accordingly, depending on assumptions regarding the coming chain of events in financial markets, TFC may be a fire-sale opportunity or a tremendous “value trap.”

How a “Niche Issue” Becomes Systemic

The consensus view appears that banks’ troubles are isolated to smaller niche regional banks. Comparatively, larger international banks are much safer and could benefit by buying assets at a discount or gaining new depositors. There is truth to this as the SPDR S&P Regional Banking ETF (KRE) lost around 25% of its value (at the Monday trough) in recent days, while the broader bank SPDR S&P Bank ETF (KBE) fell by ~19%. The gap between the most prominent global investment banks and smaller niche regional banks is even greater. Of course, a few standouts, such as Truist, lost far more than other banks in the peer group. See below:

Truist is the seventh largest bank in the U.S. by assets and is over twice the size of First Republic and Silicon Valley Bank. Compared to banks in a similar size bracket, it performed much worse over the past week, though it did not suffer nearly as significant losses as many smaller niche regional banks.

When considering the broader crisis, we must gauge how much the government’s FDIC program and the monetary system at large can handle. The FDIC, which is privately funded, had $128B in assets at the end of 2022, or ~1.27% of insured deposits. At just over 1% coverage, the FDIC can hardly handle a larger deposit crisis. Now that the FDIC is covering accounts over $250K (through the $25B backstop program), its ability to cover losses in the event of a broader run is questionable. In the US, there are around $9.9T total insured deposits and ~$19T total deposits, compared to just $2.3T total currency in circulation. Total deposits on the three failed banks (SI, SBNY, and SIVB) were around $267B at the end of last quarter, so the FDIC may already be on the hook for over $10B in losses – although it remains very unclear what the post-liquidation value of those banks will be.

In my view, the potential failure of Truist, or banks of a similar size, is a major systemic risk factor that investors should be aware of. At this point, the FDIC appears sufficiently capitalized to cover necessary losses. However, if banks with $300B+ in deposits begin to face pressure, the FDIC may not be able to cover losses, particularly if it is also requested to cover uninsured losses. It is possible that congress allows the FDIC to use Treasury assets in an “emergency” scenario. Still, taxpayer funding of the FDIC is very controversial and not legal under today’s laws. Secondly, this would require raising the debt ceiling even further.

Most importantly, the U.S. Treasury finances its deficit with funding from bank Treasury purchases. Considering banks are struggling with undercapitalization (due to unrealized losses on Treasuries), it is doubtful that banks can issue debt to the government to give back to banks. This is the broader issue facing all banks, particularly Truist, as the U.S. Treasury market has many sellers and few buyers.

Truist’s Huge “Mark-to-Market” Deficit

In my view, two fundamental risk factors are negatively impacting banks. One is realized losses on high-risk loans that are harming core equity stability. This issue is most concentrated in smaller banks with undiversified balance sheets, such as Silicon Valley Bank, which had immense exposure to loans on hardly profitable enterprises. The second risk factor is the systemic risk associated with unrealized losses on Treasury securities. This is a major risk because banks have significantly increased Treasury and agency mortgage-backed-security exposure over the past decade because they’re not counted in risk-weighted core equity leverage under Basel 3 rules. In order to encourage massive Treasury deficit financing from banks in 2020, the Federal Reserve opted to remove Treasury assets from core leverage calculations altogether.

Since Basel rules were made around 2014, there has been a steady increase in US banks’ exposure to Treasuries and a decline in cash – since they’re treated the same for CET1 ratio rules. This change accelerated in 2020 as bank leverage levels rose amid a significant increase in the money supply from QE. See below:

Unfortunately, the recent changes led banks to purchase immense Treasury assets at extremely low-interest rates, creating significant off-balance-sheet losses now that interest rates have risen. Banks also have comparatively low cash levels, higher leverage, and growing defaults due to the economic slowdown, significantly limiting their ability to cover each other’s losses. When depositors leave, or loan losses grow, banks must sell Treasuries, moving significant losses onto their balance sheet.

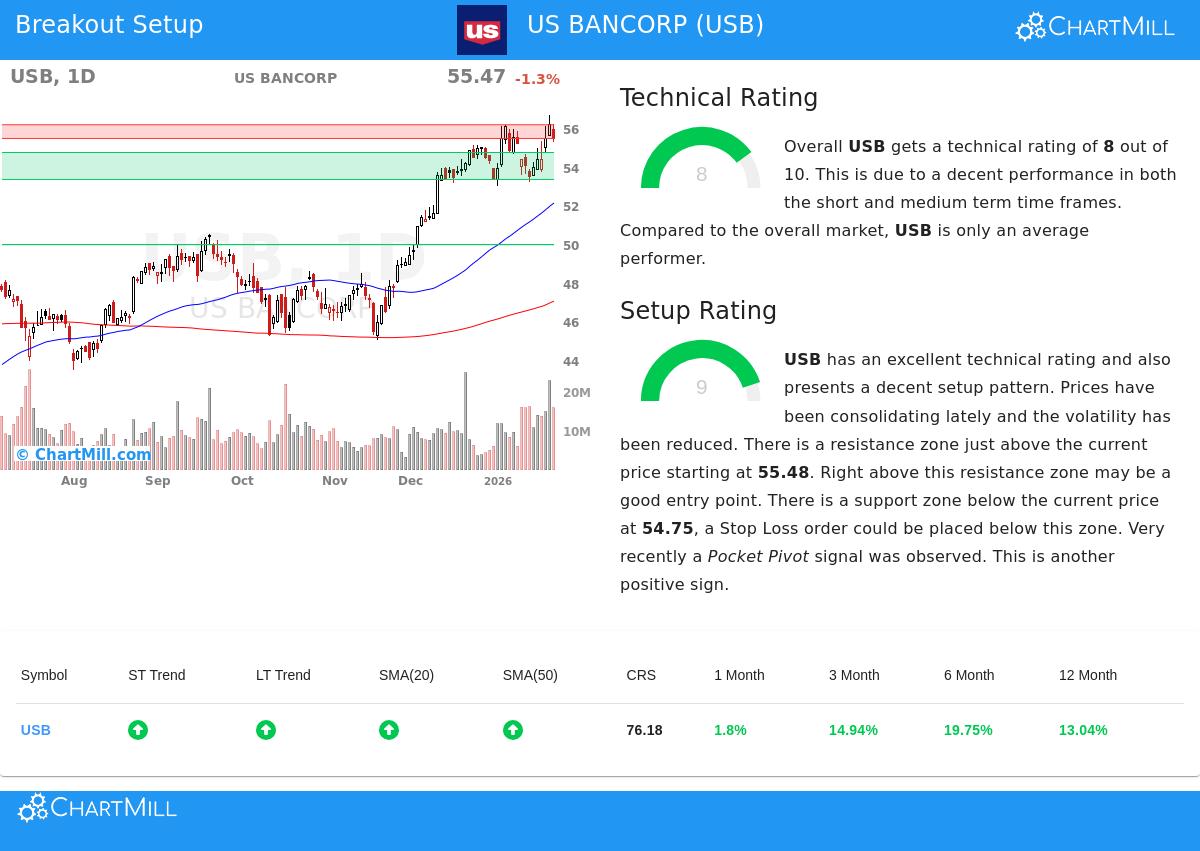

Crucially, based on JPMorgan’s research, Truist’s adjusted capitalization ratio that accounts for unrealized securities losses (primarily Treasuries and agency securities) is only around 4-5%. See below:

Adjusted CET1 Ratio for Unrealized Securities Losses (JPMorgan )

As you can see, Truist’s adjusted CET1 ratio for unrealized losses is the lowest next to SIVB. Truist’s capitalization ratio is already significantly lower than most of its peer group without adjusting for unrealized losses, but it’s greatly undercapitalized if those losses are accounted for. While these securities may fall into the “held for maturity” category, the fact is that Truist cannot hold these securities to maturity if it must raise cash – as in the case of SIVB. Of course, SIVB is unique due to the massive gap between its “official” and “adjusted’ CET1 ratio. Still, if Truist faces loan losses, its equity could be easily jeopardized, given its low adjusted capitalization. While difficult to estimate, this data implies TFC’s equity value, if it liquated all of its assets (or moved all securities to “available-for-sale”), might be around half of its “official” level.

JPMorgan’s research also noted that Truist has abnormally high loans and securities as a percentage of deposits at ~108%, a very similar level to SIVB before its collapse. All else being equal, this gives Truist higher liquidity risks in the event of a decline in security values or a rise in loan defaults. That said, JPM also noted that Truist has far fewer “high risk” depositors than SIVB or FRC, with ~60% of its deposit base being “low risk,” compared to SIVB at <10% and FRC at ~35%. This is important to remember because it implies Truist’s “run risk” is much lower than its smaller peers despite its higher overall liquidity and capitalization risk profile.

Yield Curve Inversion Compresses NIMs

Truist’s cash flows are also set to decline over the coming quarters due to the sharp rise in deposit rates. The bank ended last quarter with record net-interest margins of 3.25%, backed by an LHFI yield of 5.25% and a 0.66% deposit cost. Like most banks, Truist has significantly benefited from the rise in rates as loan yields rise disproportionately to deposit costs. However, the immense yield-curve inversion will eventually cause most banks to see their NIMs collapse. I suspect this factor is a significant negative backdrop on banks today since savings account and CD rates are beginning to rise very quickly, closing the massive gap between deposit and Treasury rates. See below:

Truist, and its peers, were in a goldilocks environment last year where rates were very high, and depositors had not sought higher yields on their savings. Today, competition for depositors is mounting, forcing banks to increase deposit rates quickly. If Truist were paying the current 1-year Treasury rate of ~5% on its savings deposits, I doubt it would have a positive net-interest margin, given that its loan yields are also around 5%.

Ongoing fears regarding bank health may accelerate the rise in deposit rates. Considering banks make riskier loans and pay depositors below the Treasury rate, objectively speaking, savers are better off moving their money out of savings accounts and buying Treasury bills. Doing so would earn a higher yield with hypothetically equal-or-lower risk considering the uncertainty regarding the FDIC’s insurance coverage. While few depositors may do this, I suspect many are moving money around, likely competitively benefiting banks with higher deposit rates. Considering most banks cannot afford to lose more than ~2-5% of their deposits, I suspect it would only take a slight change in deposit flows to increase competition for higher-return savings accounts.

The Bottom Line

Is Truist at immediate risk of collapse due to a bank run? I suspect not due to the higher quality of its depositors, the bank’s larger size and diversified loan and deposit base, and the government’s efforts to ensure a depositor backstop and qualm fears. TFC has also lost around 25% of its value over the past week and almost half its peak since 2021. Based on consensus earnings estimates and balance sheet data, it trades below its book value and at a low forward “P/E” of around 7X. TFC also has an attractive forward dividend yield of 6.5%.

Is TFC a buying opportunity? The answer depends greatly on one’s assumptions regarding the economy at large and the government’s potential role in quelling a more significant crisis. If you have a positive economic outlook and believe the government can continue to reduce concerns, TFC may be an attractive discount opportunity, given the considerable reduction in its valuation over the past week.

However, I am slightly bearish on TFC today for a few reasons. Broadly speaking, I view the current financial “crisis” similarly to a Richter magnitude earthquake scale. If we bring the risk level “one notch” higher, the crisis becomes one magnitude (or ten times) greater. The risk is not linear but exponential, as mounting pressures across the financial system could cause more banks to fail such that the FDIC does not have sufficient capitalization to cover losses – opening the door to a broader bank run. While the government’s measure to backstop $25B in uninsured losses most certainly reduces immediate contagion risks, I believe it dramatically increases long-term risks because it may leave the FDIC greatly underfunded.

In the event of an economic recession that causes loan losses to rise for all banks combined with bank cash-flows losses due to yield-curve-influenced NIM compression, many banks may soon face pressure on their loan portfolios. Additionally, falling real hourly incomes have caused savings levels to decline. This factor and the Fed’s QT program have caused all commercial banks to see deposits trend lower. See below:

To summarize, the total amount of bank deposits is falling, creating mounting pressure for less capitalized banks such as TFC. If economic pressure causes TFC’s loan losses to rise and/or its cash flows are hampered by increasing deposit rates, then it could be forced to sell its securities at a loss. Given the level of unrealized losses on its securities, a sizeable recession could likely cause the “liquidated value” of its equity to fall to or below zero.

If this were to occur, the systemic pressure would be tremendous due to potential capitalization issues at the FDIC. Hopes for additional FDIC funding are questionable since it is supposed to be self-funded. Additionally, congresses debt-ceiling battle limit its ability to provide financing if needed and will cause an immense wave of new Treasury securities to enter the market later this year once (or if?) the ceiling is raised, potentially adding to negative pressure on Treasury securities (Truist’s most significant issue). While many may assume the Federal Reserve will eventually create money to provide liquidity, its ability to create hundreds of billions of dollars (or more, as needed to cover deposits) is severely limited, given the inflation rate.

In my opinion, Truist Financial Corporation is not at high risk of immediate collapse. Further, it is not at increased risk of failure under standard economic considerations. However, if we assume a sizeable recession occurs, combined with the inability of the Federal Reserve to provide sufficient liquidity, then I believe Truist would be at material risk of collapse. Those two assumptions are certainly not guaranteed, so I would not short TFC today.

However, I think the probability of those occurrences is great enough that TFC offers a poor risk-reward profile today, even at its lower valuation. Based on the data, my personal view is that a sizeable recession is likely this year, opening the door to a broader contagion risk in banks like Truist Financial Corporation that may likely be too large for the government to manage.

Source: seekingalpha.com